To Map

To MapAthens

| As our bus entered the outskirts of modern Athens, the capital and largest city in Greece (pop. 3,096,775 in 1991), our guide pointed to the city's justly famous landmark, the Acropolis, a flat-topped limestone hill housing the remains of the Parthenon and other structures. Paul arrived in Athens by sea and landed at the port of Piraeus, three miles south of Athens, from which he also could have seen the Acropolis rising in the distance. The Acropolis has been inhabited since Neolithic times, but Athens itself became a city-state only in the mid-9th century BCE. |  |

A Brief History of AthensWhen Paul arrived in 51 CE, Athens was a small city, about 20,000, far smaller than Corinth at 100,000, and well past its prime. Still, for prominent Greeks and Romans, it was a center of learning and the philosophical pursuit of truth. The Golden Age of Athens had been in the 5th century BCE during the rule of Pericles (b.495, d.429) who transformed Athens into an imperial city at the expense of other Greek city-states. Growing in power after repulsing the first Persian invasion at Marathon in 490, Athens' powerful navy dominated the Aegean Sea and Pericles built the Parthenon, the Erechtheum, and the Propylaea on the Acropolis with tribute money he extracted from the client states of the Athenian empire. Internally, he reformed the constitution to further democracy and promoted Greek drama to its greatest expression with the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes. Other notables of the time included Thucydides and Herodotus, famous historians, Hippocrates, the patron saint of the medical profession, and Socrates, the philosopher, who refined his method in the Agora (public market place). Thus, Athens became the center of literature and art, philosophy and rhetoric, science and architecture in the ancient world.

Other city-states, especially Sparta, who had delayed the Persian army at Thermopylae in 480, envied Athenian dominance under Pericles. During the disastrous Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431-404 BCE), and a deadly plague during the war, Athens declined as a cultural center. After its defeat by Sparta in 404 BCE, although it regained its independence a year later, it never quite reached the same prominence as a world center of artistic and intellectual endeavor as before. In the unstable period following the war, Socrates was condemned to death (399) for questioning the traditional gods and thus corrupting the youth, a martyr to the freedom of reason. As the 4th century BCE progressed, Plato, Socrates' pupil, established his Academy (385) and Aristotle, Plato's student and Alexander's teacher, founded the Lyceum (335). Other philosophers, including Demosthenes and Isocrates, made rhetoric a fine art during this same time. It was, indeed, a Classic Period.

Athens lost its independence as a free-standing city-state in 338 BCE, when Philip of Macedonia took advantage of the political disunity in Greece and established control over the region. Later, in 215 BCE, Rome began to interfere in Greek affairs and, in 146 BCE, after a war that destroyed Corinth, Greek territories, including Athens, fell under direct Roman rule. Athens maintained good relations with the Romans until 86 BCE, when Sulla sacked it for supporting one of Rome's enemies. For such disloyalty, the Romans destroyed many of its monuments and left all of central Greece, including Delphi, in ruins.

Paul's Visit

Paul doesn't say anything about Athens in his letters except that he was there (I Thess. 3:1), but Luke, the author of Acts, tells an interesting story of Paul's activities there (Acts 17:16-34). According to Luke, while waiting for his companions, Paul explored the city. He no doubt visited the Acropolis, a religious shrine, for "he saw that the city was full of idols." He visited the synagogue and discussed his message with "the devout." And he walked in the Agora every day conversing with anyone who happened to be around. There, he attracted the attention of some Epicurean and Stoic philosophy teachers, the leading philosophies of the day, who invited him to speak to them.

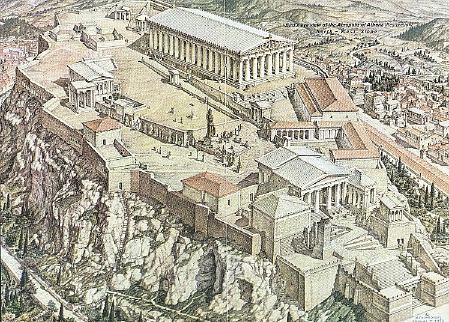

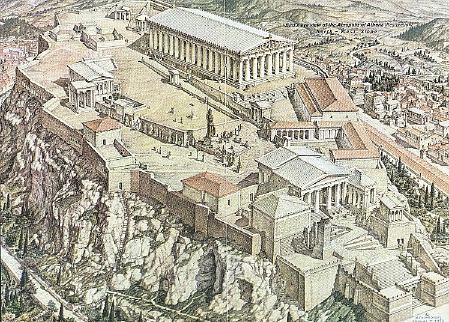

| To visit the Acropolis, Paul would have joined with other tourists and devout pilgrims and trudged up the 500 ft. hill. Emerging from the imposing entrance (the Propylaea), he would have seen the statue of Athena the Warrior, with her golden spear reflecting the rays of the sun, in front of him. To his right was the Parthenon, and slightly to his left and behind the statue, was the Erechtheum. Today, most of that scene, the several temples, monuments, altars and other sacred sites that Paul saw, we see only as ruins or as artististic reconstruction. A modern museum behind the Parthenon displays many of the artifacts of the Acropolis. |  |

| The Parthenon is the best known building on the Acropolis and was the temple of Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom and the arts and the patron goddess of Athens. Inside this 100 by 230 ft. architectural marvel was a 40 ft. gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos (the virgin). The statue Paul saw outside as he entered the area was Athena Promachos (the warrior). As the warrior goddess she always won, at least she was always on the side of the victor, unlike Ares who was simply the god of war and could symbolize victory or defeat, valor or cowardice. The Parthenon became a Christian church in 630 CE, a Moslem mosque in 1460 and survived virtually intact until 1687 when it was hit during a Venetian bombardment of the city and the gun powder stored inside it blew up.

|

| Both statues of Athena are gone, but the remains of the Erechtheum still stand. This temple, built after the death of Pericles between 421 and 406 BCE, also honored Athena as well as the traditional ancient heroes. On one side is the "Porch of the Maidens," six marble female figures serving as columns to hold up the roof. The original maidens have been moved into the museum and replaced by reproductions. |  |

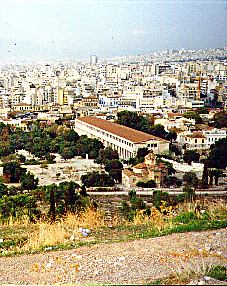

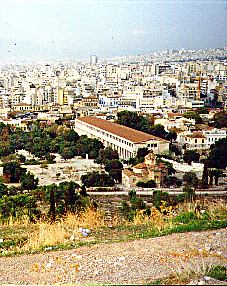

| From the Acropolis we looked down on the Agora, the public market place and administrative center, but did not have time to visit it. It looked like a public park with trees and grass, but in Paul's day it was also adorned with sacred edifices, public buildings and commercial shops, mostly around the perimeter. It served as a gathering place for conducting social, political and commercial business. Today, on one side is a long colonnaded building called the Stoa of Attalos, a replica of the original that King Attalos of Pergamum presented to Athens about 150 BCE. |

| A stoa is a colonnaded building of varying sizes that could have different purposes; a place for council meetings, law courts, offices, shops and storerooms; or an informal meeting place. The Stoa of Attalos seems to have been a shopping mall in Paul's day and is amuseum today. The Stoics took their name from stoa because Zeno (335-263 BCE), the founder, met his students in the "Painted Porch," a stoa in Athens. |  |

Paul would likely have been familiar with the Stoics because Zeno once lived in Tarsus and it was a stronghold of Stoicism when Paul was growing up there. The Stoics were concerned with moral conduct and held that the divine Logos or reason that orders all things pervades all reality. The Stoic ideal of inner serenity is achieved by attuning one's life and character to this all-powerful providential wisdom and by being indifferent to the vagaries of external events. Since all share in the divine logos, all men are brothers, and should actively participate in the affairs of the world to fulfill their duty to the human community.The Epicureans, followers of Epicurus (342-270 BCE), were not pleasure seeking hedonists, but led rather austere lives, withdrawn from worldly affairs to cultivate simple pleasures in the company of friends. They believed that fear of the gods and divine retribution after death were the source of human unhappiness. They rejected these fears because the gods were indifferent to human affairs and there was no life after death. They were often attacked as atheists because they held that sense perception was the only basis for knowledge.

| The philosophers brought Paul to the Areopagus to tell them about his "new teaching" (Acts 17:19).

The Areopagus is both a small rocky hill, adjacent to the Acropolis, and a Council with certain judicial functions which met there. The word Areopagus means "Hill of Ares," god of war. (Ares was called Mars by the Romans, therefore, "Mar's Hill.") Paul's appearance before the Council of the Areopagus, although not an official judicial procedure, "deliberately echoes the trial of Socrates for proclaiming new deities and leading the populace to question its beliefs in the traditional gods." (Oxford Companion to the Bible, p. 65). We listened to a reading of Acts 17:22-31, Paul's sermon, including the well-known reference to "an unknown god," as we stood at the bottom of the ancient rock stairs leading to the flat top of the Areopagus hill. The text is also inscribed in Greek on a bronze plaque and set in a rock at the foot of hill. Looking up at the Acropolis, that monument to imperial power and the gods who profit from it, as we listened, the words took on new life in that spot. |

Click here for a virtual tour of the Acropolis.

To Corinth

To Corinth