The minimal map of Turkey provides little clue to the geography of Cappadocia other than that it is in the center of the country (about an hour's flight from Istanbul to Kayseri). It would take a topographical map to show the mountains and even that wouldn't reveal the strangeness of the landscape. Cappadocia is not a town or city, it is not even one of the current seventy-three provinces of the Republic of Turkey. Instead it is a loosely defined area that continues the name of an ancient Roman province (look again at the Roman political map of Anatolia) and boasts a history that is as complex as its landscape.

| The topography, curious as it is, is easier to explain than is the history. Behind Kayseri is Mount Erciyes, an extinct volcano. Thirty million years ago it wasn't extinct by any means, producing immense quantifies of ash that, over the millennia, turned into soft rock, called tufa, covering some 1500 square miles of central Anatolia. Volcanos don't always spew out the same sort of stuff and so it was with Mt. Ercicyes. Some time after it had laid down the thick layer of tufa it produced lava that hardened into very much harder stone. When the volcano finally called it quits, water and wind took over and began to erode away the tufa. Great amounts of it were literally blown away but where it was held down by the heavy stone above, it stayed in place. One of the results is what today's romantics called "fairy chimneys," remembering folk tales about people being carried off by fairies when they strayed too far into what was a volcanic wasteland. |  |

The curiosity about what happened here, and when, was piqued, not more, by the short stay in Cappadocia. It was fortitious, therefore, that there appeared, shortly after our return to the United States, an article by Robert G. Ousterhout in Archeology Odysseyentitled "Cappadocia's Mysterious Rock-Cut Architecture." This article is well worth reading for it addresses many of the questions that naturally come to mind when visiting Cappadocia -- or even just looking at some pictures of it. The accompanying time-line also is important.)

| Before going to the four "visual memories": a note about influence from the region on the development of Christian doctrine. Paul may not have passed through Cappapocia but, one way or the other, 300-400 years later there was an active Christian presence, one energetically opposed to the Arian "heresy." The Cappadocian Fathers--Basil the Great, bishop of Ceasaria; Gregory of Nazianzus; and Gregory of Nyssa (seen here in an 11th-century mosaic in the church of St. Sophia in Kiev) -- were influential in the defeat of Arianism at the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE. Their writings have remained bulwarks of Orthodox theology through the centuries. |

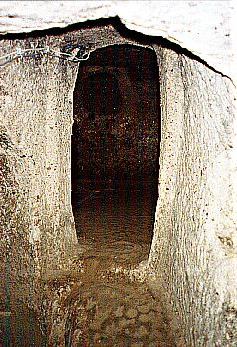

1. Underground Cities.

There are dozens of these multi-story underground dwellings, two of which (Derinkuyu and Kaymakli) are open to the public. Who begun the digging of these caverns and tunnels is a mystery, but there are those who think the first levels were built as storage areas by the Hittites as long ago as 1400 BCE. They were periodically used for security from invaders, perhaps by Christians eluding Romans and, later, Arabs. Local villagers hid in them from an invading Egyptian army in 1839.

|  |  |

|  |

| Today the underground cities are tourist attrractions and archeological sites and, for the moment, residents have no need to hide in them. Instead they live in houses set on the hillsides or in homes carved from the tufa. Tufa, easy to cut, becomes concrete-like when exposed to air and therefore ideal for troglodyte living. Some of the tour group enjoyed an evening at a nightclub cut from the soft volcanic stone! For more information see this interesting PDF document. |  |  |

2. Rock Churches

Valleys in Cappadocia are honeycombed with caves that contain fantastic "negative" artechiture, that is structural elements, such as columns and arches, that mimic that of free-standing buildings but have only decorative functions in a cave. Many, though not all, of these "buildings" are churches.

|  |

|  |

|  |

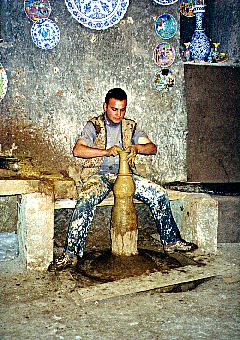

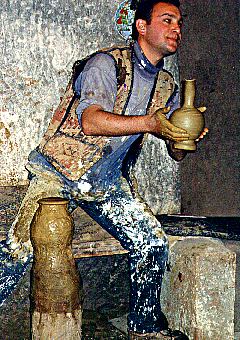

3. Potters and Pots

Every civilization has its distinct type of pottery, so the archeologists say, and Cappadocia is far from the exception. The soil, the clay, of the region is exceptional and thus encourages potters from ancient to modern times. Several establishments that specialize in contemporary pottery welcome visitors, not only to display and sell their wares but to demonstrate how they are made:

|  |  |

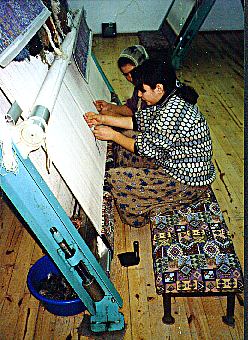

4. Carpets

The finest Turkish carpets are made in Cappadocia and there, so it is said, are to be found the best bargains in carpet price. They are made in much the same way they were made in Marco Polo's time and of the same materials: wool. cotton, and silk:

|  |

|  |