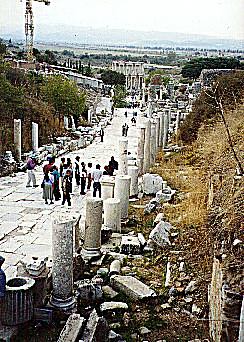

Paul began his first visit to Ephesus where we ended ours--at the theater. He would have landed at the ancient port of Ephesus and walked the mile or so east toward the city along Arcadian Street facing the theater. We began our visit at the eastern end of this ancient city ruin, walked west down Curetes Street, also called the Marble Road, and ended our tour at the theater. The harbor is no more and the coast line is several miles away due to silt deposits from the Cayster River over the centuries. About a mile to the north of the theater along the Artemision Way is the location of what was once one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Temple of Artemis of the Ephesians. The guide did not even bother take us to see the scant remains, the foundation and a single column, from a temple known to be four times as large as the Parthenon.

A Brief History

Ephesus, in contrast to Corinth, was old, about 1,000 years old, when Paul arrived in the summer of 52 CE. Founded by Athens as a colony in the 10th century BCE, its historical origins are clouded in myth. For a brief period it was under the control of King Croesus of Lydia until Cyrus, the Persian King, defeated him in 547 BCE. The Persians controlled the city about 200 years until Alexander captured it in 334 BCE. Then it became a Greek city for about 200 years until the Romans acquired it along with all of the province of Asia from Attalos III in 133 BCE, the king who gave the Stoa to Athens.

| The Lydian influence in Ephesus produced a thoroughly mixed culture, part Greek, part Asiatic, more than anywhere else in the Greek East. Alexander's successor, Lysimachus (ca. 290 BCE), walled the city and parts of' the wall are yet visible. The city collaborated with Mithridates VI, king of Pontus, in his revolt from Rome in 88-85 BCE. A major incident was a one-day slaughter of 80,000 Roman residents of Asia. Ephesus paid a high price, along with other Greek cities, as Rome retaliated to regain domination in the east. The city had also ceremoniously welcomed Antony and Cleopatra in the winter of 32-31 BCE, on their way to defeat at Actium in September of 31. Still, beginning immediately with Augustus' reign (27 BCE), Ephesus entered an era of prominence and prosperity which lasted into the second century CE. Augustus made it the capital of the Roman province of Asia and it received the coveted title, "First and Greatest Metropolis of Asia." Imperial patronage included constructing aqueducts, paving streets, and enlarging agoras. During the Augustan era Ephesus was the largest commercial center in Asia, in fact, the third largest city in the Empire, after Rome and Alexandria, with a population of about 200,000. Its location was one of the many reasons for its commercial growth. The Royal Road, build by the Persians to run from Ephesus to Susa, the Persian capital, made it a gateway to and from the interior. The Romans used milestones in the city as the point of origin for measuring distances in Asia. |  The Mazaeus & Mithridates Gate leading to the agora, built in Honor of Augustus and his wife Livia by two slaves whom they had freed. Click for a detail. |

The Third Ecumenical Council was held in Ephesus in 431 CE and Justin Martyr, the first Christian philosopher, was converted there.

Not the Goths, not river silt, but earthquakes and malarial mosquitoes finally finished Ephesus sometime between the 6th and 10th century. The site was completely abandoned after the 14th century.

Paul in Ephesus

According to the Book of Acts (18:19-21), Paul's first visit was merely a stopover on his way to Antioch, Syria. In Acts' version he returned overland to Ephesus from Antioch and visited churches that he had established in Galatia and Phrygia along the way (18:23; 19:1). Once back in Ephesus, Paul settled down and conducted his ministry here for over two years (19:10). Some scholars think that Paul may have moved directly from Corinth to Ephesus and set up shop without returning to Antioch. Whichever, Ephesus was the center of his missionary activities for at least 27 months, perhaps 3 years (20:31).

With Ephesus as their base of operation, Paul and his associates spread the Christian Gospel into the adjacent cities and regions of Asia. His choice of Ephesus made sense because it was big, cosmopolitan, multicultural, and a political, economic, and religious center, a meeting place for people, goods, and ideas from all over the Mediterranean. Such diversity of culture, cult, and ethnicity was not benign but spawned culture conflict, simmering hostility and ethnic hatreds.

| The story of Paul in Ephesus is told in Acts 19:1-20:1. Acts says that he went first to the synagogue, but Ephesus has yet to yield any synagogue remains. From there he moved to the hall of Tyrannus for his ministry of preaching and healing. Paul called his hearers to join a new community, one stripped of ethnicity, and built on self sacrifice and mutual helpfulness. Out of almost three years, Acts details only two incidents to highlight what Paul encountered in Ephesus. The city was known as a center for magic and miracles and the first story is about itinerant Jewish exorcists who tried to heal in the name of Jesus as Paul did, but were unsuccessful (Acts 19:13-16). Later a number of converted magicians burned their books on the magic arts. (19:19). The second incident was the near riot in the theater prompted by the silversmiths' protest against Paul. According to Acts, Paul was so successful ("the word of the Lord grew and prevailed mightily" - Acts 19:20) that he threatened the livelihood of the craftsmen who made silver souvenirs of the Temple of Artemis and sold them to the foreign tourists and pilgrims. Most of the Greek and Egyptian pantheons were present in Ephesus, but Artemis was the patron goddess. Scholars disagree about what she represented, but she seems to have been an amalgamation of the Greek Artemis, the virgin goddess of chastity, and an ancient mother goddess. One source said that the goddess' religion was not characterized by base sensualism or focused on sexuality and fertility, but that it was internationally recognized as a premier religion which appealed to both the social need and personal pietism of the Ephesians. |

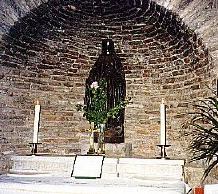

| Scholars seem to agree that Paul wrote four of his letters from Ephesus: Galatians, First Corinthians (part of an ongoing correspondence with the Corinthians), Philemon, and Philippians. The latter two, he wrote while in prison in Ephesus. Second Corinthians seems to have been written while Paul was on the road after he left Ephesus. Post-New Testament tradition holds that John, the disciple of Jesus, brought Mary, the mother of Jesus, to Ephesus to live and wrote the fourth gospel there. In his later years, according to tradition, John was exiled to Patmos, wrote the Johannine Epistles, the Revelation, and combated Gnostic heretics. We visited the traditional site of "Mary's house," now a venerated shrine. |  |

| The Temple of Artemis underwent fundamental evolution and expansion in its 1200 year history. King Croesus was the primary benefactor of the classic temple. Only the most meager evidence is available about the pre-Croesus temples. He donated most of the columns for the temple that mad King Hesostratos burned in 356 BCE, the night Alexander the Great was born. Ironically, Alexander helped restore the temple to its prior splendor. The Temple standing when Paul resided there was the largest edifice in Greek antiquity, 227 X 422 ft., with 127 columns, each approximately 6 ft. in diameter and 65 ft. high. The temple was so rich and prosperous that it became, with the temple in Jerusalem, one of the world's first banks. Goths sacked it in the Third Century CE and Christians plundered it in the sixth century taking many of the original columns to Istanbul to build the Haghia Sophia. |

| We began our tour at the eastern end of Curetes Street, so called because the names of the priests (curetes) were found on the bases of columns at the beginning of this street. First, we walked through the State agora (Public Square), which didn't look like more than a large open space (about 190 X 520 ft) a few steps below ground level. In Paul's day, however, it was the center of civic life with government offices and imperial shrines surrounding it. On the north side, between the municipal palace and the council house, a theater type structure called the Odium, where the city council met, are the remains of a double temple of Roma and Julius Caesar. In front of the municipal palace are the Doric columns where the names of the Curetes are inscribed. Running the length of the agora in front of these key civic buildings was a Royal Portico (a covered walkway) dedicated to Artemis, Augustus and Tiberius. In the center of the square was the Temple of Augustus. As you leave the square to the west, on your left are the ruins of a temple venerating the Emperor Domitian, built after Paul's visit. Incorporating the temples and shrines of the imperial cult into the civic space of the city shows how inseparable were religion and politics and how religious observance promoted allegiance to the empire. Moving right along down Curetes Street with more for the eye to see than the brain can process, you pass the Hercules Gate and a fountain honoring the Emperor Trajan. You snap a picture beside a relief of the goddess of victory, Nike. |  |

| A little farther west along Curetes Street lies "Hadrian's temple," constructed no later than 127 CE, after Paul but again reminding you of the continuing strength of the imperial cult in Ephesus. On the front arch, the keystone is a bust of the mother goddess Cybele and on a semicircle in the back is a relief of the head of Medusa. Beyond Hadrian's temple are remains of the public baths, public toilets, and a brothel. The most significant dwellings so far excavated are the so called slope houses, residences of the wealthy, located across from the temple of' Hadrian on the South side of Curetes Street. They are being reconstructed and are due to open before our next visit. |

| However, the most impressive structure in the restored city is the facade of the Library of Celsus. Built long after Paul was there (between 115-125 CE) by a son to honor his father who was the governor of the province of Asia, it is thought to represent the standard monumental form of the Roman library. It faced the East, probably for better lighting, and contained a collection of less than 15,000 rolls, small compared to Pergamum or Alexandria. Between the library and the theater, carved in one of the paving stones of the street is an advertisement for the brothel . The Goths destroyed the library when they invaded in 265 CE. |  |

The ceremonial gates to the right of the library were built in honor of Caesar Augustus before Paul arrived (see photo near the top of this page). Through the gates was the commercial agora, the main marketplace of the city. Shops with arched roofs surrounded it on all sides. An Egyptian temple of Serapis stood just beyond the SW corner and was later adapted for Christian usage. Like many other large cities in the ancient world, Ephesus' religious climate included a plethora of Greco-Roman and Egyptian deities.

| The theater, seating 24,000, was built in the Hellenistic period but Claudius, Nero, and Trajan made major structural changes during their reigns to bring it into line with the ideal Roman theater. The alterations included deepening the stage by extending its front edge 20 feet and enlarging the orchestra so that animal fights and gladiatorial combat could be accommodated. Commenting on these brutal spectacles of people torn and devoured by wild animals or killed in mortal combat for entertainment value, Rodney Stark says simply, "It is difficult to comprehend the emotional life of such people." (The Rise of Christianity,p. 214) However widespread the notion is, there is no historical evidence that Paul ever preached in the theater. The only text that mentions Paul and the theater says explicitly that he did not go into the theater to preach and defend the gospel (Acts 19:30). |

More details on Ephesus may be found here.