To Turkey Map

To Turkey Map

To Greece Map

To Greece Map

Istanbul

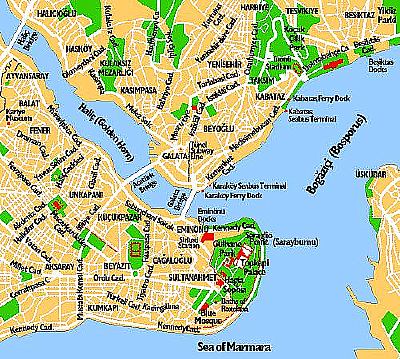

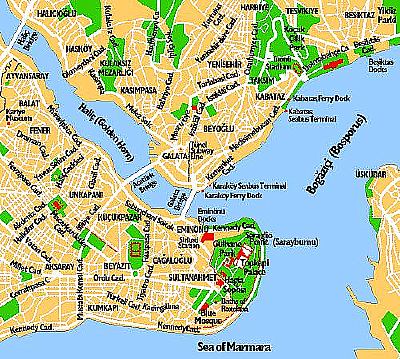

It is indeed audacious to write about Istanbul after less than forty-eight hours in the city and rainy hours at that. For Istanbul is an immense city with such a long and complex history that attempting to separate out and identify the remainders of the various centuries requires...well, it requires return visits, more than one. Nevertheless, the value of seeing a city with a tour lies in the overview one gets, an overview that stands in good stead the next time round. And so perhaps these notes may be justified for what they might offer for the next traveller's first visit. | Nothing is more important than a map, not so much for absolute positions as for relative ones. Where is the Blue Mosque relative to Hagia Sophia? Can you walk to the Topkapi Palace from the Spice Market? Where is "Europe"? "Asia"? The map at left is a beginning for answers to these kinds of questions but, first, let's put the map itself into a larger context. The old city is on Seraglio Point, the tip of a peninsula surrounded by "the three seas": the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Golden Horn. The former two we know, but what is a golden horn? The Golden Horn is a 7-kilometre-long inlet that some of the earliest inhabitants thought was shaped like a deer's horn, thus the name. The prosaic modern name is the Haliç (canal). The Golden Horn is lined with warehouses, docks, and a historical ruin now and then. Across the Golden Horn to the north is the "new" city and across the Bosporus to the east are the portions of the city that lie in Asia, where the modern city's upperclass has built it's own palatial structures, complete with docks for ocean-going yachts. With the exception of a boat trip on the Bosporus, this first visit was limited to the major tourist destinations in the old city. |

Istanbul needs to be located in history as well as geography. Its long early history included occupation by Athens, Sparta, Athens again, and threats from Celts (3rd cen. BCE), Alexander, etc. The history relating to what may be seen in Istanbul today, however, begins with the Roman emperor Constantine, who, in 330, moved the capital of the empire from Rome to the ancient town called Byzantium, first renaming it New Rome and then Constantinople.

With the collapse of the western Roman Empire, the eastern empire centered in Constantinople continued, as the Byzantine Empire, in one form or another until 1453 when the city fell to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, who continued to maintain the capital in Constantinople, now gradually beginning to be known as Istanbul, a permutation of a Greek term meaning "in the city"; the official name remained Constantinople, however, until the Turkish Post office officially changed it to Istanbul in 1930. The Ottoman Empire survived until it collapsed in World War I and was replaced by the current Turkish Republic, founded in 1923 by Mustafa Kemel Atatürk, who moved the capital to Ankara, where it remains today.

| Constantine first permitted Christianity and other religions to practice freely and then gave preference to the Church, to the point of settling theological controversies (e.g., Nicea 325). Had it not been for Constantine who knows what would have happened to Christianity? It could well have gone the way of Mithraism, and today's Christians could be making sacrifices in the temple of Jupiter or (more likely?) trekking down to the synagogue on Friday night to practice a Judaism that, without doubt, would be radically different from the Judaism we know. It could reasonably be argued that Constantine had more influence on western civilization than anyone else, not even excepting Jesus or Paul. The construction of Hagia Sophia (photo at right) was ordered by Justinian and, after five years during which marble was brought from hither and yon, columns pillfered from ancient sites all over the empire, the building now standing (though much repaired and restored after repeated earthquakes and desecrations by crusaders and others) was opened on 27 December 537. It was preceded by the church begun by Constantine in 325 and by the second built in 415 by Theodosius II, both of which were destroyed by fire. |  |

The name, Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) began to be used in the fifth century and was corrupted by the Turks to Ayasofya, the name used today for the museum the church has become. The minarets were added when the building became a mosque. Many other refinements were added during the Middle Ages; Istanbul became thoroughly Muslim, its Christian past relegated to historical memory. The priceless mosaics inside Hagia Sophia, incidentally, were plastered over and only recovered in modern times by historians who were no longer dealing with sacred space, either Christian or Muslim.Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque (see below) were constructed alongside the ancient hippodrome that was begun in 203, enlarged by Constantine I in 325, and used for chariot and other horse races. During the Crusades the metal statures around the hippodrome were smelted down to make coins. After the Turkish conquest some of the former splendor was restored, however today only three of the ancient monuments remain.

|  | The Egyptian Obelisk (right) was brought from Egypt by the Emperor Theodosius I in 390. It originally had been erected at the temple of Karnak at Heliopolis by Tutmosis III. The hieroglyphs tell the story of the pharoah's military victories and depict him sacrificing to Amun-Ra. The base, however, is not Egyptian. There, on one of its faces, Theodosius is depicted watching the obelisk being set in place; on another he and his family watch chariot races. The inscriptions are in Greek and Latin. Constantine's Column (far left) is thought to date to the fourth century when it was covered with bronze plaques. What is more certain is that in the tenth century Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrgenatus restored the masonry column and modestly installed an inscription on the base reading "Constantine restored this now ruined monument to a state better than the original." Such restoration, however, could not withstand the onslaught of the Crusaders who, in 1204, tore off the bronze and melted it down. The Serpent's Column (near left) is another Byzantine import to Constantinople, this time from Greece. Part of a monument commemorating a Greek victory over the Persians in the fifth century BCE, the three entertwined snakes held a golden cauldron on their now missing heads at the temple of Apollo at Delphi. One of the heads now resides in the British Museum while a second is in the Istanbul Archeological Museum. It is possible, though not certain, that the column was imported during the time of Constantine I. |  |

A short walk from Hagia Sophia is the Sultanahmet Mosque, the so-called Blue Mosque because of the blue tiles on its interior. Begun in 1609 and finished in 1616, the mosque was located opposite Hagia Sophia intentionally to be a more splendid counterpart to the great Byzantine church. It has six minarets instead of the four that are usual for sultans' mosques, because the ruler who ordered it built, Ahmet I, was the sixth sultan after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople. It is said that, in order to silence critics, he provided the funds to build a seventh minaret in Mecca so that his mosque would not have more than did the holy city.

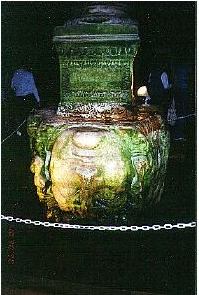

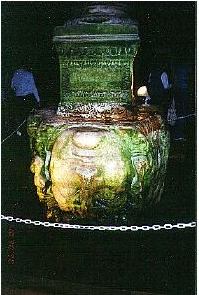

Sultanahmet (Blue) Mosque| We naturally assume that water running from our faucets indicates how much further "advanced" we are compared with other civilizations. Well, running water was important to the citizens in Constantinople/Istanbul, too, especially since the city had to prepare constantly for the next siege. The water system of the ancient city was concentrated in a series of cisterns, one of the largest of which is a covered cistern not far from Hagia Sophia called Yerebatan Sarnici (Yerebatan Palace) or the Basilica Cistern. Open to the public, it is a refreshing change from the steady round of museums. Originally constructed in the early fourth century (Constantine I), the cistern was restored and enlarged by Justinian in the sixth century. The superstructure is supported by 336 columns in twelve rows among which tourists saunter on board walkways while classical music and innovative lighting surround them in a kind of surrealistic son et lumièreas they catch glimpses of fish swimming near their feet. Fish, which were featured in the cistern from its early days, were re-introduced when the structure was drained and cleaned in the mid-1980s; some 50,000 tons of mud were removed. To everyone's surprise, two of the columns were found to be supported by massive sculpted heads of Medusa from some unknown Roman temple. The upside down heads obviously were considered nothing more than convenient blocks of stone by the cistern's builders. Originally holding something like 10,000 tons of water, the cistern was connected by an underground waterway to the Topkapi Palace but, according to legend, was closed eventually to stop the traffic in stolen women and other goods. |

|

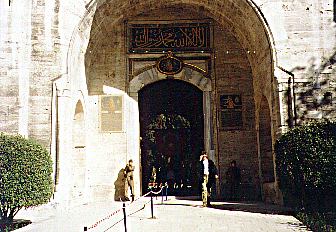

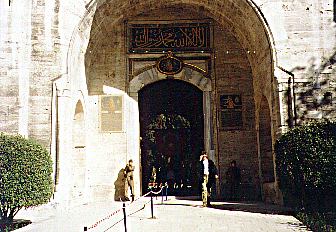

| The construction of Topkapi Palace, which is actually a complex of buildings, was begun about 1472 by Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II and additions continued until the middle of the 19th century. Entered through a massive ceremonial gate, the complex was the center of Ottoman government and the residence of the sultan, his family, and entourage until the 19th century. The riches of this museum may only be suggested by a list of some of its buildings in four main courts: the kitchens with 12,000 pieces of porcelain, including rare Chinese gifts to the sultan; the Treasury with a wealth (literally!) of jewels and golden objects, not to mention some bones originally belonging to John the Baptist; the Pavilion of Holy Relics includes Mohammad's footprint, tooth, lock of hair, and a hand-written letter, plus swords belonging to four of the caliphs; the circumcision chamber with blue-green tiles; and more and more. Click here for details about the Topkapi Palace Museum on the web. |

| For shoppers nothing compares with the Grand Bazaar, an immense covered maze of streets teeming with shops of every variety, offering everything from carpets to tempting jewelry and furniture. The Bazaar was begun in the 15th century soon after the city was conquered by the Sultan Mehmet and galleries have continued to be added ever since. The shopping continues at the Spice Bazaar, where the mix of fragrances brings home the reality of the orient to Western senses. |  |

| Among the host of hotels at all price ranges in Istanbul, one has a particularly affinity for mystery: the Hotel Pera Palace. Built around the turn of

the century, it boasts an over 100-year-old elevator. But that's not the mystery. The mystery lies in the fact that it hosted mystery-writer Agatha Christie who may have written Murder on the Orient Expressthere.

The rooms have the

names of celebrities who stayed in them on the door, including, in addition to Christie, such luminaries as Ernest Hemingway. There is a story

that, during WW II, spies from the US, Great Britain, France, Germany, and

Italy lived on separate floors but ate together in the hotel dining room. |

Every tour of Istanbul concludes with a boat ride on the Bosporus where sights of ancient fortifications sit side-by-side with rotting wooden buildings, evidence of commerce, and the constant reminder of the debt that modern Turkey owes to Mustafa Kemel Atatürk. To Cappadocia

To Cappadocia