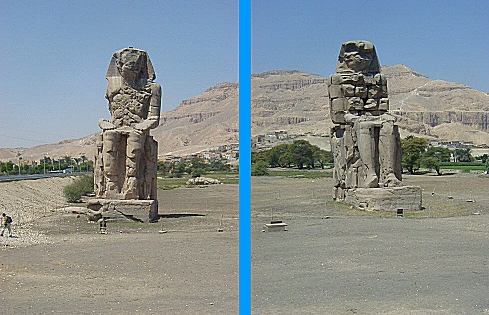

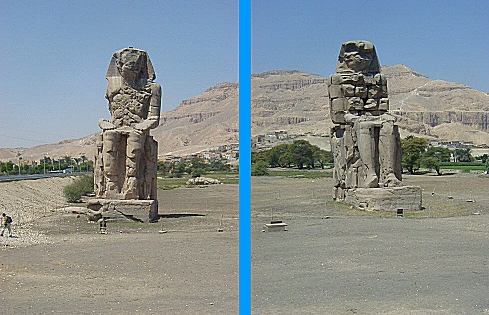

The mortuary temple of Amenhotep III (Dynasty 18, 1386-1349 BCE) was, in its time, the largest temple complex in Thebes, covering almost 90 acres. Today all that remains are these two badly damaged statues of the pharaoh that stand alone beside the road leading to the edge of the desert from the Nile. The tour bus stops only long enough for tourists to get out and snap a few pictures before hurrying on to more "interesting" sights. But ancient tourists lingered longer, as graffiti in Greek and Latin on the bases of the statues give evidence. Dubbed the Colossi of Memnon by ancient Greeks who knew nothing of Amenhotep III, these 64-foot tall monoliths were thought to be images of the warrior Tithonus and Memnon, son of Eos, both of whom had fought at Troy. It didn't detract from their appeal to tourists that the northernmost statue, due to a crack caused by an earthquate in 27 CE, seemed to sing when the wind blew. In the 3rd century someone "repaired" the stature and it ceased to sing. Maybe that's why the tour bus only stops for ten minutes.

The most famous of the Theban mortuary temples is that of Hatshepsut, the queen who became king (Dynasty 18, 1498-1483 BCE). Called Djeser-djesru (Holy of the Holies) in antiquity and set in the natural amphitheater known as Deir el-Bahari today (Northern Monastry in Arabic), the temple is a building that would not be out of place in a catalogue of the works of Frank Lloyd Wright. In reality it was probably the work of Hatshepsut's friend and advisor, Senenmut, who based it on the foundation begun by Tuthmosis II (Hatshepsut's husband/brother) and the design of the now ruined temple of Mentuhetep II (Dynasty 11, 2055-2004 BCE), the ruins of which lie immediately to the south of Djeser-djesru.

| The temple walls tell wonderful stories of Hatshepsut's divine birth and of her adventurous journey to the mysterious land of Punt (certainly somewhere in Africa-south-of-the-Sahara). This first-time visitor continued to marvel that color remained after so many millennia. The fascinating story of Hatshepsut, of how she ruled jointly with her very young step-son, Tuthmosis III, and then assumed the kingship for herself, of how the effort was made to obliterate memory of her by defacing her monuments and destroying her temples -- all this is told by Joyce Tyldesley in Hatchepsut: The Female Pharoah. |

| There are many "faces" of Hatshepsut. In some she is depicted as a man, complete with false beard. In others she clearly has a female figure but is dressed as a male king. Here are two of those faces. On the left, on the exterior of her temple, is Hatsheput as Osiris. And on the right is the remnant of a colossal statue in the Egyptian Museum at Cairo in which she appears as someone we today might like to meet. | > |