Tanis, in the eastern Delta, was a capital and necropolis for the kings of the 21st and 22nd dynasties (1069-715 BCE in the Third Intermediate Period) and was a thriving commercial center until the rise of Alexandria under the Ptolemies. The ancient Egyptians knew this city as Dja'n, while to the Hebrew prophets Isaiah (19:11 & 13; 30:4) and Ezekiel (30:14) it was Zoan. Today's maps show it as San el-Hagar. Ancient Greeks called it Tanis.

Most commentaries on the intact royal tombs found at Tanis attribute the lack of excitement at their discovery to the overriding concern of World War II–certainly that conflict was more important than ancient Egyptian tombs, no matter how lavish. But I suspect that the failure of the Tanis finds to compete with the splendors of "King Tut" in later years is due, to some large degree, to their provenance in the Third Intermediate Period in the eastern Delta and not in the New Kingdom at Thebes. And, too, it may have something to do with Ramesses II.

| A bit south of San el-Hagar is Qantir, a village where once a great city stood, the capital of Ramesses II and his namesakes of the 19th and 20th dynasties. There's precious little of Pi-Ramesse (Per-Ramesses; Piramesse) left today. The ravages of time did their part, but the principal despoilers of Pi-Ramesse were those very same rulers of the 21st and 22nd dynasties who were sent on their last journeys in silver coffins. So the Ramesside stones, statues, and obelisks came to Tanis and lie in the ruins for us to photograph today. There is no way to escape Ramesses II.  |

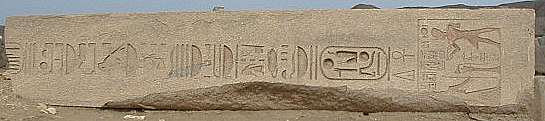

| No scenes depicting Ramesses' "victory" over the Hittites at Kadesh have been located at Tanis but an inscription that commerated the many years later Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty was brought to Tanis by the Libyan pharaohs of the 21st-22nd dynasties. The treaty was "sealed" by the marraige of the king and a Hittite princess. And there she is (though badly damaged) standing beside the massive leg of a colossus of Ramesses II. The hieroglyphic inscription not only identifies the bride as Hittite but announces that she is "Great King's Wife." This was no ordinary wife and the treaty was no ordinary treaty. (Thanks to Lee Coats for help on this inscription.) |  |

Lest we allow Ramesses II to have the last word (as it seems he usually does when it comes to monumental Egypt), it is well to remember that the fallen colossi, columns, and various building blocks scattered over the modern-day archeological site at one time formed a city from which kings who were not Ramesses ruled Lower Egypt for over 300 years. The foundations that are revealed are their foundations. And it is the city of Psusennes I and Sheshonq II that is still being unearthed by French archeologists and their brightly dressed Egyptian helpers.