The "Chaco Phenomenon"It doesn't happen often but occasionally a phrase will appear that seems just right from the beginning. Such a phrase is "the Chaco Phenomenon," which was first used by the excavator of Salmon Ruins, Cynthia Irwin-Williams (Vivian and Hilpert 2002:133f). Dictionaries list such words as "unusual" and "marvel" in defining "phenomenon"; Chaco Canyon was nothing if not unusual and marvelous. The Canyon's great houses, great kivas, attendant unit pueblos, and roads in themselves merit the appellation, "phenomenon." But when you add in the social, economic, religious, and—perhaps most significant—political system that was centered at those great houses and kivas during the 11th and 12th centuries, "Phenomenon" merits a capital P.

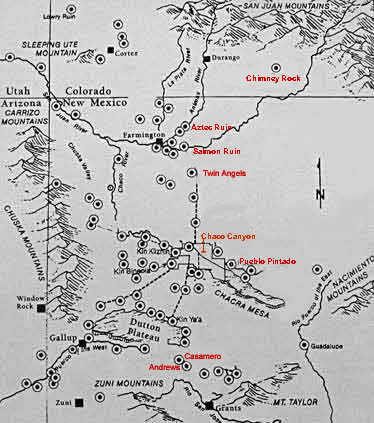

The map also traces the main road system, which is actually much more extensive than shown here. Though it might be possible to argue that the outliers were separate communities that utilized a universal Anasazi construction manual, the existence of the roads points to them being directly related to Chaco. In fact, the roads hold the Chaco Phenomenon together (Lekson 1991: 48). But were the roads merely roads? Were they roads at all? I'd like to leave those obviously important questions hanging for the moment to slip in a sentence or two that raise other, related, unanswered questions. Students of these matters have suggested at least two answers to the question of who built the Chaco structures that are not in the Canyon: (1) They were built by people from Chaco as satellites, outposts in a trading network or, perhaps, as indicators of cultural dominance (more about that possibility later). (2) They were built by people in local pit house communities to imitate what they had seen in the "big city" and so capture for themselves some of the cosmopolitan glamor. Maybe they employed architects from Chaco to show them how to do it. Or did Chaco "architects" force the locals to build that way? No matter that these questions may remain forever debatable, what is certain is that an intimate relationship existed between downtown Chaco and communities throughout the San Juan Basin and beyond in the 11th and 12th centuries.

The Great North Road Two of the largest great houses, Salmon Ruin and Aztec Ruins, are outliers, though they play such a special role in the Chaco Phenomenon that "outlier" hardly seems to apply. In order to get to Salmon, and then to Aztec, the Chacoans traveled the Great North Road (at least the ones who traveled in the first half of the 12th century, when the road was built). As a glance at the map above reveals, the road leads directly north from Chaco Canyon (actually from Pueblo Alto on the mesa above Pueblo Bonito) to just short of Twin Angels Pueblo. Concrete evidence for the road ends at the bottom of a stairway into Kurtz Canyon, through which it is presumed to have continued to Twin Angels and, from thence, to Salmon Ruin. Though evidence on the ground is lacking for a resumption on to Aztec Ruins, many archaeologists believe it almost had to be there (Lekson 1999: 116). The North Road is perhaps the most clearly defined of all Chacoan roads. Furthermore, it is one of only two or three Chacoan roads that actually goes some distance to somewhere; the vast majority of the roads so far discovered connect close-together great houses or even just go a short distance into the wilderness and simply stop. Could it be that not all roads are equal? That some roads were for traveling and some roads…well what? What need did a society without wheeled vehicles or beasts of burden (other than humans) need for 30-foot wide roads? Several explanations have been offered: they facilitated transport of the huge timbers that were brought from distant mountains for great house and great kiva construction in the Canyon, they allowed armies to march across country, they "integrated" the Chaco world, they served some kind of unknown ritual purpose—maybe all, some, or none of these. No answer is fully satisfactory. But, particularly for the Great North Road, it would seem to me that traveling, integration, and ritual could apply. For one thing, this road is straight, straight north. It not only is wide, with multiple "lanes," but it doesn't go around obstacles; it goes over hills and fills in valleys. It is as though the Chacoans were obeying the biblical injunction to "make straight in the desert a highway" (Is. 40:3) for whatever gods they served. The road angled northwest past Twin Angels to get to Salmon but then, if it continued to Aztec, it went straight north again. People certainly traveled the Great North Road—though not on a daily basis, judging from the paucity of ceramics and lithics found on and near it (Roney 1992: 124)—but its main purpose was not to make it easier to walk from Chaco Canyon to Salmon Ruin. Like the great houses and great kivas at its either end, the Great North Road was an integral part of the Chacoan "ritual landscape" (Stein and Leckson 1992). |